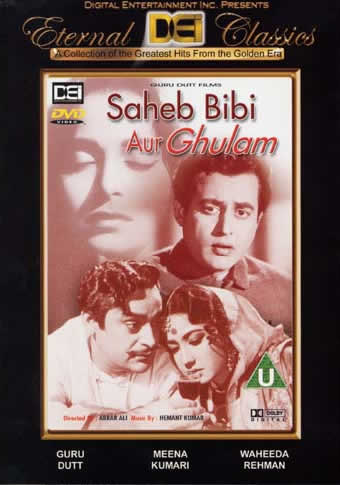

SAHIB BIBI AUR GHULAM

(“Master, Wife, and Servant,” Hindi, 1962, 154 minutes)

Directed by Abrar Alvi

Produced by Guru Dutt

Based on a novel by Bimal Mirta; Dialogues: Abrar Alvi; Music: Hemant Kumar; Lyrics: Shakeel Badayuni; Cinematography: V. K. Murthy

Although credited to longtime Dutt collaborator Abrar Alvi, this haunting masterpiece is unmistakably Guru Dutt: a chiaroscuro meditation on time, memory, and social and personal injustice in the great tradition of PYAASA and KAGHAZ KE PHOOL. Unlike those two films, however, this one’s central figure is a woman, and Dutt’s own character, Bhootnath (“Lord of Phantoms,” an epithet of Shiva that is especially appropriate here), is less a conquering (or conquered) “hero” than a mute and helpless witness to her tragedy. As always in a Dutt film, that individual tragedy has far wider ramifications.

Told in flashback as the memory of an engineer who is supervising the demolition of a once-stately Calcutta haveli (mansion) belonging to the old landed aristocracy of Bengal, the plot moves along two counterposed trajectories: one traces the rise of Bhootnath, a naïve but educated villager who comes to Calcutta to seek his fortune and gradually acquires training, self-confidence, and even love, to eventually attain a comfortable middle class status — indeed to become the supervising engineer of the frame narrative. The other storyline follows the decline of the Chaudhury family in whose mansion Bhootnath first found shelter – the mansion he will eventually see destroyed, but which he remembers in all its splendor, bustle, and periodic outbursts of cruelty. Its presiding males, two brothers who occupy themselves with such traditional aristocratic pursuits as pigeon-keeping, elaborate “marriages” of pet cats, and drunken nights in high-class brothels, regularly abuse their tenants, servants, and wives. The intersection of these two narratives is one of the latter, the beautiful Choti Bahu (“the young daughter-in-law” – unforgettably portrayed by Meena Kumari) who is “not like the other wives” in the family and who, during her nightly abandonment by her whoring husband, sings of her longing (Piyaa, chale aao — “Beloved, come back”), and eventually confides in Bhootnath, drawing him into her misery and her still-cherished hopes.

Helped by a schoolteacher friend who has been in the city for some time (and who, we later learn in a weakly-developed subplot, has a double life as an anti-British terrorist), Bhootnath finds employment in the “Mohini Sindoor Factory,” which manufactures the auspicious vermillion powder (sindur) that married women apply to the part of their hair to affirm their suhaag or protection by a living husband. There he quickly earns the trust of Mr. Suvinay, the factory’s owner, and a member of the Hindu reformist sect Brahmo Samaj (which was influenced by Protestant ideology and which sought to “purify” Hinduism of “superstition,” “idolatry,” and customs such as sati or widow immolation). Suvinay’s drawing room, with its upright piano, lace curtains, and puranic figurines in European porcelain, is a plausible encapsulation of bourgeois Brahmo syncretism, as is the dress of his daughter Jabba (Waheeda Rehman) – a white sari worn over a long-sleeved bodice, to which it is pinned with a cameo-brooch. Yet this prim progressivism is evidently not stifling for women, for Jabba, though clearly an adoring daughter, is also a spirited girl who knows her own mind. She likes Bhootnath from the start, flirts openly with him, and eventually squelches a planned marriage to the son of one of her father’s Brahmo cohorts. The chemistry between Dutt (who actually looks younger here than in the earlier PYAASA) and the vivacious Rehman is palpable – the two were allegedly lovers at the time – but their characters’ union is repeatedly and significantly deferred to allow the film to explore other themes.

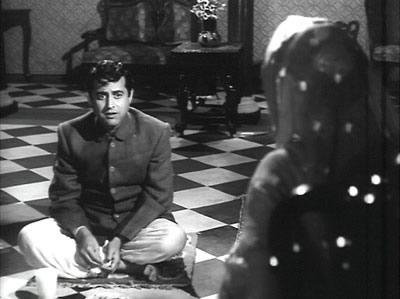

The sunny parlors of middle-class progressivism are contrasted to the dark, confining interior rooms of the haveli, to which Choti Bahu repeatedly summons Bhootnath. What at first appears as an attempted seduction – a love-starved housewife noticing a strapping new boarder in one of the outbuildings and calling him secretly to her boudoir – is revealed as a touching and pathetic attempt to win back her husband’s affection by securing a tin of Mohini Sindoor. When this fails, the lonely wife turns to more desperate measures, and begins a downward spiral into depression and alcoholism that viewers, like Bhootnath himself, can only watch in helpless sorrow. After the sindoor factory closes and Suvinay dies, Bhootnath receives a breakthrough job supervising an engineering project that takes him away from the city for a lengthy period. He returns to find the Chaudhury estate a shambles due to the brothers’ unwise investment in a coal mining scam, but the occupants still lost in their fantasy world of refined and decadent pursuits. In this decaying world, only Choti Bahu still clings to a hope for redemption, and enlists Bhootnath’s help in a last, doomed effort to save her now-paralyzed husband and restore the family fortune.

Colonial-era discourse in India was much preoccupied with what was termed the “woman question” — a critique of the treatment of women in Indian society that was voiced both by British officials and Indian reformers; for the former, it reinforced the argument against Indian readiness for self-rule. The effect of Katherine Mayo’s journalistic exposé Mother India (1927), which luridly articulated this argument and became a bestseller in England and the United States, led to defensive nationalist rejoinders that still echoed in the post-Independence period — indeed, in the epic film MOTHER INDIA (1957), which deliberately hijacked Mayo’s title in the service of its paean to the glories of Hindu motherhood, self-sacrifice, and fiercely-maintained chastity. Dutt’s approach to the subject is, as usual, rather different. His potential model of the New Woman is not a rustic husband-worshiping pativrataa, but the educated and independent-minded Jabba, who emerges from the shadows of sorrow over her father’s death and separation from her beloved (exquisitely picturised in the song Meri baat rahi mere man men — “My unspoken words lie sealed in my heart” — in which the lighting on Jabba repeatedly fades from day to night) to seek and ultimately find a companionate marriage to the man she loves. Yet her radiant fortune is overshadowed by the fate of Choti Bahu, shockingly revealed in the film’s final moments, which confirm that the latter was indeed its central figure.

The schizophrenic division to which upper-class women were so often subjected — into respectable wives whose job was to produce male heirs and uphold family honor, but who received little education, were largely confined to the inner household, and were not regarded as entertaining or glamorous companions, and courtesans who (at their best) were highly sophisticated career-women and artists who moved about freely, but who were denied social respectability and the long-term security of marriage —is bluntly articulated, in two scenes, by Choti Bahu’s husband as he prepares to depart for his favorite brothel. The psychological violence wrought by this division has been explored, from the supposed point of view of the tawayaf or courtesan, in a number of famous films (cf. PAKEEZAH, UMRAO JAAN). In SAHIB BIBI AUR GHULAM, however, the kotha (brothel) scenes are confined to brilliantly choreographed set pieces (such as the memorable song Saqiyaa, aaj mujhe nind nahin aaegi — “Friend, tonight I shall not sleep”), and the inner lives of the public women are never explored. But in Choti Bahu, Dutt and his writers offer us a complex character who is vainly trying, within the cage of decaying patriarchal gentility, to overcome this divide. Not content to (as her husband tells her) “Do as the other daughters-in-law do: acquire jewelry, sleep, play games,” Choti Bahu fiercely pursues her ideal of loving companionship by seeking to be everything to her husband — pious wife, emotional confidante, and playful mistress — repeatedly humiliating herself in the process. Though we want her to find the love and understanding she so desperately seeks, her ultimate failure seems less a critique of her effort than of the corrupt and brutal male world in which she is trapped. At film’s end, Bhootnath’s hard-won bourgeois life remains irrevocably haunted by her beauty, idealism, and anguish.

As a story about the decline of the old landed zamindari families of Bengal, Guru Dutt's film explores, using the great director's preferred idiom of popular and surrealist cinema, some of the same themes that had been the subject of Satyajit Ray's realist artfilm JALSAGHAR ("The Music Room," 1958). Though Ray's film is likewise a powerful achievement, Guru Dutt's uses the brilliant score of Kumar and Badayuni and the matchless b/w cinematography of V. K. Murthy (extraordinarily displayed, for example, in the courtesan dance sequence noted above, in which a brightly-lit soloist pirouettes in front of a shadowed ensemble and against a backdrop of gleaming neoclassical nudes — a dazzling display of revealed and concealed femininity, that alternates with the leering gaze of the patron) to produce, to my mind, an even more complex and disturbing film about social decay and social change.

[The Digital Entertainment Incorporated (DEI) DVD of SAHIB BIBI AUR GHULAM is of variable but generally good quality—far superior to the Yashraj Films DVDs of PYAASA and KAAGAZ KE PHOOL—and offers good subtitles for both dialogue and songs.]

For additional reading: Nasreen Munni Kabir, Guru Dutt: a life in cinema (Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). This sensitive tribute to Guru Dutt contains a fascinating chapter on Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam, including the reminiscences of several close associates of the director.