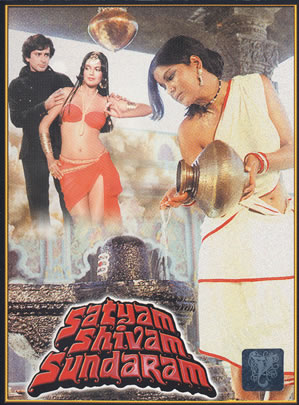

SATYAM, SHIVAM, SUNDARAM

(“Truth, Holiness, Beauty”)

1978. Color. Hindi. 172 minutes.

Directed by Raj Kapoor. Music by Laxmikant-Pyarelal; lyrics by Anand Bakshi et. al.

Ironically, Raj Kapoor’s extended meditation on the contingency of beauty and desire was much criticized for its “vulgarity” and “exploitation” of women’s bodies. It unfolds, in fact, like an Indian folktale costumed by Fredericks of Hollywood. Set in the imaginary Madhya Desa beloved of Bollywood, where feathered tribals gyrate erotically to celebrate the opening of a dam that will bring them prosperity and progress, it displays bevies of village belles who are low on both modesty and blouse-pieces, and a tragic heroine who cannot afford even the latter. The aptly-named Rupa (“lovely form or appearance,” played by Zeenat Aman) has a beautiful body and voice, but half her face is disfigured by scars from a childhood cooking accident, and she is scorned by the villagers as “unlucky” and unmarriageable. Enter Rajiv, a handsome, nattily-dressed engineer from the city (Shashi Kapoor), who “hates ugliness” but falls in love with Rupa by hearing her singing, and then by seeing only the half of her face that she unveils. Reasoning that the relationship can have no future, Rupa permits herself the fantasied satisfaction of being wooed by Rajiv, but is horrified when he asks her father for her hand. The ceremony transpires with Rajiv still ignorant of Rupa’s scars, until the inevitable wedding-night unveiling.

It is here that a folktale logic takes over, since Rajiv doesn’t merely reject his disfigured bride, but accuses her, over the denials of the whole wedding party, of being an evil substitute for the “beautiful” woman he wooed. Fleeing his bedroom, he rushes to the waterfall where he and Rupa used to meet. In time, Rupa herself, unable to surrender either of their fantasies, repairs there with her former half-veiling to begin a passionate “adulterous” affair with the very husband who despises and rejects her by day. Though the situation is dreamlike, the emotional power of Aman’s sorrowful heroine—forced to split herself into two in order to preserve a man’s illusions—is very real, and infects even a torrid lovemaking scene. Predictably, Rajiv’s bride, though ostensibly trapped in an “uncomsummated” marriage, is found to be pregnant—the kind of conundrum that, in a folktale, calls for a deus ex machina. Kapoor obliges by making the heavens literally open in a flood of near-Biblical proportions, underscoring the film’s underlying association of women with nature and men with civilization and artifice—a theme that, like the Shakuntala motif of the unrecognized and rejected woodland bride, resonates through a number of Kapoor films. Though the director’s climactic vision strains the limits of his special effects budget, everyone who isn’t drowned ends up, in a ruined Krishna temple, mud-spattered but clear-sighted—able to face “truth” and recognize true beauty.