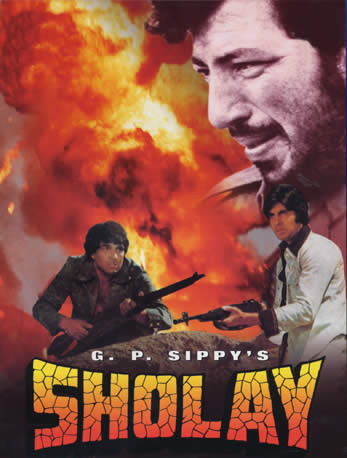

SHOLAY ("Flames")

1975, Color, Hindi, 199 minutes.

directed by Ramesh Sippy.

Screenplay: Salim Khan, Javed Akhtar; lyrics: Anand Bakshi; music: R. D. Burman; cinematography: Dwarka Divecha

From unpromising beginnings (typically, industry insiders predicted that “unconventional” elements in this big-budget film would make it a resounding flop) Sholay exploded onto 70mm screens to become one of the Bombay film industry’s greatest success stories — the film that would, for vast audiences, definitively embody the masala blockbuster. Released on August 15th (Indian Independence Day) 1975, it played to sold-out houses at major urban venues such as downtown New Delhi's huge Plaza Cinema for more than two years, becoming the highest-grossing Indian film ever made, a laurel it held for nearly two decades. It is indisputably one of the most influential Hindi films of all time, and the question to ask Indian cinephiles is not whether they have seen it, but how many times?—answers in the double digits are not uncommon. Indeed, so popular was it that not only its songs, but its stylish dialogs were issued on audiocassette, and can still be recited by fans throughout India. One of the films that helped make Amitabh Bachchan the ‘70s superstar par excellence, Sholay also catapulted Amjad Khan to stardom in the role of the sadistic bandit Gabbar Singh, and is said to have ushered in the era of the “supervillain.” While giving a quintessentially Indian turn to the now-international mythos of the Western, Sholay also set new standards in cinematography and action sequences—as in the spectacular opening train scene.

The film’s entertainment value holds up well, as does its cinematic craft, and so it remains a fine vehicle for introducing novice Western viewers to the phenomenon of the "masala film." Literally meaning "spice," masala commonly refers to a blend of multiple spices (as in "curry" powder), and cinematically to an action-adventure-romance that is expected to offer a three-hour multi-course banquet of emotional flavors, encompassing slapstick comedy, romance, violent action, social and family melodrama, and of course, a half dozen or so song-and-dance sequences. First-time Western viewers sometimes find such combinations indigestible—a disquieting emotional roller-coaster ride through genre terrains that "properly" belong to three or four different films. Another unsettling trait is the Indian filmmakers' apparent tendency to "quote" motifs or images from Western cinemas (e.g., Sholay's pop-critical label "curry Western,” and its obvious citations of Charlie Chaplin, Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah, and of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid). Again, novice viewers often see this less as homage and creative adaptation than as ludicrous and uncomprehending copying of "original" Hollywood ideas, resulting in a chaotic pastiche. Yet the fact that scores of masala films are produced each year, including a handful of hits, suggests that the genre has, for receptive audiences, an aesthetic logic of its own. As the most acclaimed film of this genre, Sholay is useful for raising as well as problematizing cross-cultural cinematic stereotypes.

Synopsis: A train arrives at a rural station and a lone police officer disembarks, looking for "Thakur Sahib" (thakur, literally "lord, master," is a respectful title for a member of one of the landlord castes who trace their lineage to ancient kshatriyas or warrior-aristocrats; Sahib means "sir"). As the credits roll, we follow his horseback journey through a Badlands-like landscape to the remote settlement of Ramgarh (“Rama’s fort”). Here he meets the Thakur, Baldev Singh (Sanjeev Kumar), a retired police officer who is always wrapped in a gray shawl. Singh requests his visitor to locate and bring him two criminals, the scruffy, ever-smiling Veeru (Dharmendra) and the lanky, brooding Jaidev or “Jai” for short (Amitabh Bacchan). When the officer asks what task these notorious repeat-offenders can possibly be suited for, Singh recounts his first meeting with them, two years earlier, when he was transporting them to jail via a freight train. Immediately after they boast to him of their courage, the train is attacked by bandits, and they defend it and their wounded captor against a seemingly unending troop of horsemen. But their moral ambivalence is revealed when they toss a coin to decide whether to bring the bleeding officer to a hospital (landing themselves in jail), or to escape (leaving him to die). In a motif that will be repeated, "chance" impels them to do the Right Thing. The flashback ends with Singh's visitor promising to search for the pair, but adding that, if they are out of jail and at large, it may be difficult to locate them.

Cut to the first musical number: Veeru and Jai steal a motorcycle with sidecar and burst into a rollicking "song of the road," evoking the antics of Raj Kapoor's "vagabond" persona of the 1950s (cf. Awara, Shri 420). Here, however, it is not simply a celebration of manic, vaguely anti-social freedom, but an ingeniously choreographed male love-duet, as they affirm their eternal friendship (dosti) during a joyride through a scenic obstacle course dotted with banyan trees and hapless rustics.

We next see them approaching a crooked but comical Muslim lumber dealer, Surma Bhopali (Jagdeep), with an unusual offer: he will turn them in to the police, collect the reward of 2000 rupees, and split it with them when they are released from prison. Cut to the prison, and another ludic interlude, including homage to Chaplin's Great Dictator in the crackpot jailer (comic actor Asrani), who boasts of his training under the British. The wily pair easily outsmart him and escape, but when they return to Bhopali to collect their promised thousand rupees, he betrays them to the police. Back in jail, they are located by the Thakur's agent, and Singh awaits them outside the prison gate when they are released, thus ending the comic digression and returning to the frame narrative. Singh asks them to capture the notorious outlaw (daku) Gabbar Singh; in return, he will give them the 50,000 rupees reward offered by the police. He pays them a 5,000 rupee advance, and promises another 5,000 when they reach Ramgarh.

Arriving by train, the boys encounter a talkative female tonga (horsecart) driver named Basanti (Hema Malini). Jai is bored by her ceaseless chatter but Veeru is entranced. Soon after reaching Ramgarh, Jai catches a glimpse of Radha (Jaya Bhaduri, Bacchan's future wife), the Thakur's daughter-in-law, who wears a widow's white sari. Having received their 10,000 rupees from the Thakur, and having glimpsed the riches in his safe, the duo plan to rob the household by night and make a quick exit. But as they prepare to do this, Radha confronts them, offers them the key to the safe, and tells them to take her jewelry (emblematic of the auspicious state of a married woman) as she has no more use for it. They are shamed into dropping their plan.

Enroute to picking green mangoes for her elderly aunt, Basanti helps a blind maulvi (Islamic preacher) descend a hill—thus demonstrating that communal harmony reigns in Ramgarh. He asks her to help convince his only son, Ahmad, to take a job in the city, although this will mean leaving him alone in his old age. In the mango grove, Veeru and Jaidev shoot down green fruit for Basanti, and Veeru "teaches" her to use a pistol.

The village routine is shattered when dacoits arrive, demanding their tribute of grain. The Thakur refuses to pay, and aided by Veeru and Jaidev, drives them away. They return to Gabbar Singh (Amjad Khan), who metes out sadistic punishment for the failure of their mission.

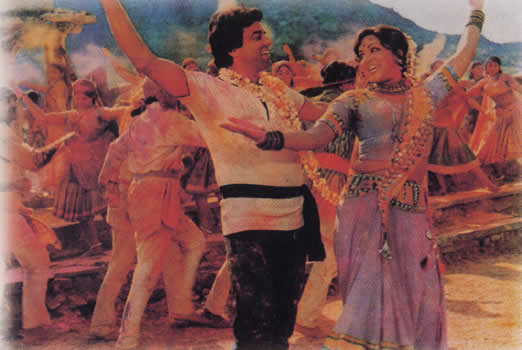

Cut to a scene of Holi festivities in the village (the spring harvest festival of fertility and licentiousness, and a stock trope in many Hindi films; cf. the similar scene in Mother India); amidst a rain of colored powders and dyes, Veeru and Basanti dance and sing a saucy duet, but Jai can only gaze at the somber Radha from afar. The festivities are interrupted by a brutal attack by Gabbar's band, who almost kill the heroes, but are at last driven off. Afterward, Veeru's disgust at the Thakur's failure to assist them at a crucial moment (by tossing them a gun) leads to a long flashback, in which he explains the cause of his helplessness and his enmity with Gabbar Singh. (Intermission)

When Veeru and Jaidev, horrified by the Thakur’s tale, vow to kill Gabbar Singh, the Thakur reminds them that he wants the outlaw alive. A villager brings news that gypsies—known to supply arms to the dacoits—have arrived in the area. Cut to a dance sequence in the gypsy camp, featuring the hypnotic song Mehbooba (“Beloved,” sung by R. D. Burman himself), with sensual (to Indian ears) Middle Eastern-style music and heavily Persianized lyrics. While Gabbar Singh is distracted by the show, Veeru and Jai enter the camp. In the ensuing skirmish, Jai is wounded. As he returns home, Radha rushes to meet him and the Thakur realizes her feelings.

The blind maulvi receives a letter from his urban brother, informing him that he has found a job for Ahmad; however, the boy refuses to leave his aged father. It being Monday, Basanti goes to a temple to ask Shiva for a good husband (as unmarried girls typically do). Veeru briefly impersonates the deity, but is found out. As Basanti drives away in anger, Veeru sings to her "Anger makes a pretty girl even prettier." Veeru now tells Jai that he wants to marry Basanti, and asks his buddy to intercede with her aunt. Jai finally does, but the aunt is horrified by Jai's description of Veeru's lifestyle of drinking, gambling, and whoring. Rejected, Veeru gets drunk and threatens to kill himself by leaping from the village watertank. The dialog to this famous scene includes comic asides on Veeru’s use of English.

1st villager: Brother, what is this "suicide" thing?

2nd villager: You see, when English people croak, they call it "suicide"!

At last, Basanti's old aunt relents and agrees to the match.

The blind maulvi's son Ahmad, departing for his new job in the city, is waylaid and murdered by Gabbar's men as revenge for the Holi debacle. His dead body carries a letter from Gabbar, threatening worse retaliation if Veeru and Jai are not surrendered to the dacoits. As the old maulvi weeps over his dead son, the villagers angrily tell the Thakur that they cannot take any more; a debate ensues over nonviolence versus fighting back. But the maulvi shames the villagers by asking Allah why He didn't give him more sons to sacrifice as “martyrs” for the village. Veeru and Jai proceed to the rendezvous point, and manage to outwit and slaughter Gabbar's men.

Back in Ramgarh, the Thakur's old servant tells Jai how happy Radha used to be before the massacre—leading to a flashback to another Holi scene, when her wedding was being negotiated. Jai resolves to ask for her hand, and the Thakur goes to Radha's father, urging that, although a widow, she be permitted to begin a new life. The men agree on this.

Basanti is pursued by Gabbar's men, and Veeru tries to save her. Both are captured. In a famous scene, Gabbar forces Basanti to dance in the hot sun, threatening to shoot her lover if she stops. She sings, "I will dance as long as there is breath left in my body." At one point, the dacoits make her dance on broken glass (recalling the climactic dance sequence in Pakeezah). Needless to say, Jai comes to the rescue, the dacoits are slain, Thakur Baldev Singh takes his revenge on Gabbar, and (some of) the lovers live on happily.

Sholay presents interesting parallels with its predecessor by nearly two decades, Mehboob Khan's Mother India, notably in the enduring trope of the daku (Indian English "dacoit") or highwayman—an outlaw whose popular representations span the gamut from freedom-loving Robin Hood to rapacious sociopath. In the earlier film, the mother's dark, younger son Birju, driven by well-justified hatred for the parasitic village moneylender who has ruined the family, eventually becomes the leader of a dacoit band; he appears as a dashing, richly-dressed horseman, who is primarily interested in settling a score against feudalistic oppression; yet when he finally abducts the moneylender's daughter, his own mother rises to destroy him. In contrast, the dakus of Sholay—from their first appearance in the flashback of the train-shootout—are unambiguously evil and bent on carnage, yet they are apparently ensconced in the very heart of the nation (the film's visual setting is the plateau country of the northern Deccan, India's midsection), and the forces of social order (here focused in the brooding patriarch, Thakur Baldev Singh) are powerless to defeat them. Indeed, the sadistic Gabbar Singh has brutally murdered this "Father India's" two sons and has literally cut off his law-administering arms (cf. the comparable though "accidental" mutilation of the father in Mother India). To strike back, Singh must (as he puts it) "use iron to cut iron," replacing his slain offspring and severed arms with two "adopted" criminal “hands,” who alone possess the requisite bravery (and moral ambivalence) to track down the monster in his lair.

Significantly, a mere six weeks before the premiere of Sholay, on June 26 1975, another self-styled "Mother India," Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, claiming that anti-social forces imperiled the nation and that draconian measures were required to prevent chaos, imposed a "State of Emergency," suspending constitutional rights and jailing thousands of political opponents. In retrospect, Sippy’s cinematic epic appears as a surprisingly dark and prescient parable of the erosion of traditional order and the brutalization of politics in the once-happy village of Ramgarh—the Nation writ cinemascope.

Sholay has been the subject of two book length studies to date. Wimal Dissanayake and Malti Sahai's Sholay, a cultural reading (New Delhi: Wiley Eastern, 1992), attempts a comprehensive scholarly study that sets the film within the broader history of popular cinema in India. Anupama Chopra's Sholay, the making of a classic (New Delhi, Penguin Boooks India, 2000) is an inside look at the film's production, based on interviews with the director, stars, and crew members.