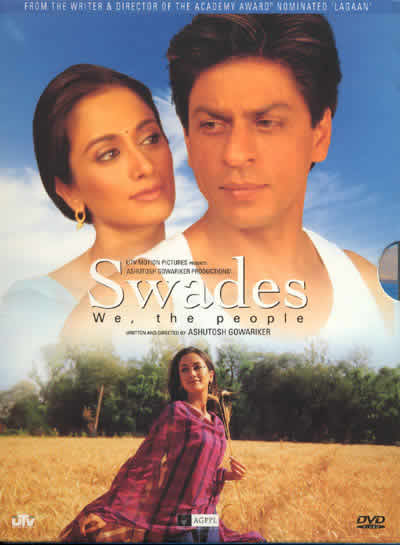

Swades

(notes by Corey K. Creekmur)

[“Our Country” or “Homeland”: the film’s “official” English subtitle is “We, the People”](2004), Hindi, 195 minutes

Produced, Written and Directed by Ashutosh Gowariker

Story by M. G. Sathya and Ashutosh Gowariker; Dialogs: K. P. Saxena; Music: A. R. Rahman; Lyrics: Javed Akhtar; Cinematography: Mahesh Aney; Starring: Shah Rukh Khan, Kishori Ballal, Gayatri Joshi.

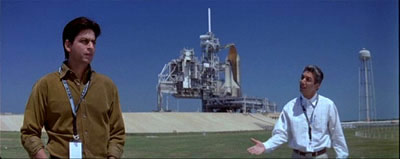

After the international success (including an Academy Award nomination) of Lagaan (2001), writer-producer-director Ashutosh Gowariker’s follow-up is at first glance a very different film: whereas Lagaan gave new life to the Hindi “historical” film by being located entirely in 1893 and in Champaner, an imaginary Indian village, Swades opens with a shot of the globe that zooms down into contemporary Washington DC, where its hero, so unlike the earlier film’s simple villager Bhuvan, is a manager working on NASA’s Global Precipitation Measurement project. Whereas Bhuvan, lacking the ability to converse in English, nevertheless has to learn the wily ways of the British colonial rulers in order to literally beat them at their own game, Mohan Bhargava (Shah Rukh Khan), the hero of Swades, is apparently a fully assimilated, literally globalized scientist who skillfully handles a press conference in high-tech, jargon-laden English. And whereas Lagaan begins with the imposing voice-over of Amitabh Bachchan’s immaculate Hindi, that language won’t be heard in the “Hindi” film Swadesfor almost ten minutes, and then as hybrid “Hinglish” spoken by Mohan and his colleague Vinod.

But Swades soon draws Mohan back to his native India and to Charanpur, another imaginary village, in search of his beloved Kaveriamma (veteran actress Kishori Ballal, most notable in Kannada theatre, film, and television), the humble woman who raised him but who he has shamefully neglected following the death of his parents in a car crash when he was in college. Once the film adds a romance with Gita (Gayatri Joshi in her film debut), a village belle and schoolteacher of the feisty and independent sort, and begins to focus upon a goal (the generation of electricity from a local water supply) that brings the entire village together, the successful shadow of Lagaan falls more broadly over this film, despite the gap of a century between their settings. More ambitiously, both films seek to define “Indianness” through collective action spurred by a hero, but where the previous film required translation into the context of the present, Swades functions as direct commentary on current conditions. Moreover, whereas the earlier film depicted its hero and heroine as a Victorian-era Krishna and Radha, Swades relies on the now more ideologically charged invocation of Mohan and Gita as a modern Ram and Sita. (However, the requisite association of Shah Rukh Khan with the naughty boy Krishna is made here, albeit briefly, when he teases his “second mother” by identifying her as the god’s mother Yashoda when they meet again after many years. The romantic song, “Saanwariya Saanwariya,” will also later identify Mohan as Gita’s “beloved” “dark one.” On the whole, however, Swades represents another step in the relatively recent on-screen maturation of Shah Rukh Khan, who at age forty id finally shedding some of his popular persona’s persistent and even grating boyishness.)

On one eventful day, Mohan Bhargava publicly announces the beginning of Phase II of the NASA project he supervises, learns that his application for U.S. citizenship has been approved, and informs his friend Vinod that this is the anniversary of his parents’ death. This sad memory also recalls Kaveriamma, and so Mohan requests a vacation from his boss to visit India and locate the woman who was a second mother to him.

Arriving in Delhi, Mohan finds that Kaveri is no longer in the “old folk’s home” where he had left her, but has moved to a small village called Charanpur; after a chance encounter in a bookshop, a serious young woman, who upbraids customers who do not esteem books as sources of knowledge, provides Mohan with what seem to be unusually precise directions to the village. (Can any viewer wonder whether they will meet again?)

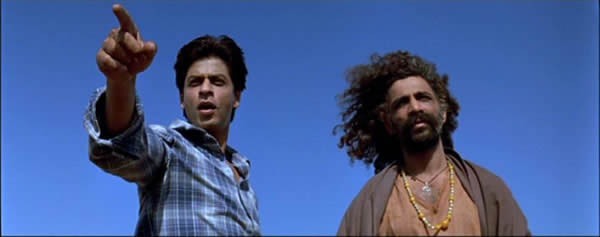

Mohan then rents a fully equipped “caravan” (recreational vehicle) and sets out with the radio playing old Hindi film songs, a first sign that this diasporic citizen of the world is returning to local roots despite his high-tech trappings. However, according to a sadhu met on the roadside, Mohan has “strayed off the path.” With this literal but slyly spiritual guide, Mohan’s direction is regained through the film’s lively first song, Yun hi Chala Chal Raahi (“Go on, O traveller!”), which itself cleverly travels from the caravan’s radio to the throats of the two men (or, at least, their playback singers).

The film’s first song sequence thus relocates Mohan in the landscape of India as well as within the Hindi film tradition of “songs of the road” that establish film heroes as carefree wanderers: with a slight twist to that tradition, the guilt-burdened and deadline-driven Mohan cannot simply declare himself a free traveler, but must learn to become free – and Hindustani – through uninhibited song and dance, brokered by his (half-mystic, half-Bob Marley-esque) guide.

After his massive vehicle squeezes its way into the village, Mohan and Kaveriamma are reunited, and he discovers that she is now raising two other orphans, young Nandan (known as Chikku) and his sister Gita – are vah! the very girl from the bookshop! – who Mohan actually knew as a child and playfully called Gitlee. The film’s first important dilemma – will Kaveri go to America with Mohan, or remain to care for Gita and Chikku? – is perhaps familiar but, to the film’s credit, is treated as a genuinely complicated and emotionally difficult decision for all involved, including the audience, who are left to worry about the problem during intermission.

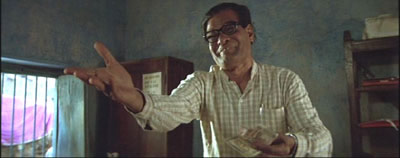

As Mohan’s plans to leave India with Kaveriamma are delayed and as his attraction to Gita grows, he meets the local villagers, including Navaran Dayal Shrivastava, postman and wrestler (and Hanuman devotee), Mela Ram, a cook who dreams of establishing a string of dhabas on American highways, and Dadaji, the beloved village elder and a former freedom fighter. While subtle, Swades is rather remarkable for introducing vivid rather than stereotypical characters who represent the caste dynamic that organizes the village: Shrivastava’s status as an amiable but forward-looking Kayastha, for instance, positions him as a crucial intermediary in the film’s unfolding exploration of social divisions and alliances. Mohan also comes to better understand the life of the village itself after attending its panchayat (community meeting) and learning of local conflicts regarding the electricity supply and the future of Gita’s school; he also discovers that the village is named for the foot (charan) prints of Ram and Sita at a local temple: in other words, the village (like the film itself) is literally imprinted by myth.

Mohan’s initial role as a silent observer begins to change once he defends Gita’s rejection of an arranged marriage that would force her to abandon her career; however, his “outsider’s” criticism of India’s problems and blind adherence to tradition are challenged by Gita herself. In attempting to increase the number of the school’s students in order to save the school, Mohan also encounters class and caste prejudices that he dismisses as backward, but even if the film implies the audience’s agreement, it respectfully rather than mockingly allows village leaders to question Mohan’s right to criticize their beliefs and behavior. (The film thus stages a genuine dialog between traditional and changing views of Indian society, unlike the many Indian films that hyperbolically stage but don’t really explore this tension.)

Along these lines, one of the film’s most interesting scenes involves the outdoor screening of a Hindi film: the raised screen literally divides the village by caste (with lower caste villagers forced to view the image reversed), though the collective pleasure of seeing Yaadon ki Baaraat (“Union of Memories,” Nasir Hussain’s hit film from 1973 about three separated brothers, written by Salim-Javed) apparently momentarily overrides such discrimination. Indeed, popular cinema’s unifying potential is emphasized, and reaction shots of the crowd depict the responses of different audience segments, as when Zeenat Aman’s performance of R. D. Burman’s hit song “Chura liya hai tumne jo dilko” generates wolf-whistles from a group of men.

However, with yet another electrical failure in the village, the film stops and Mohan takes the stage, literally removing (with the help of the energized Shrivastava and Mela Ram) the barrier between the groups while demonstrating that individual stars in the sky, however bright, are no match for the constellations they form (in this case a plow, with echoes of Mother India, among other classic films) when linked together. The message of unity here relies upon light sources perhaps more symbolically powerful than the beam of a film projector, but Mohan’s performance, which moves into the song Yeh Tara Wo Tara (“This star, that star …”), is of course a conventional Hindi film moment that cleverly fills in the (here unanticipated) interval of a Hindi film. Although disdainful of many Indian traditions, Mohan has apparently kept up with the “tradition” of Hindi film song sequences, and draws upon their admirable tradition of inclusiveness.

Generally, however, for the first half of the film, Mohan finds village life in India to be backward (with married women expected to quit working, and child brides deprived of education altogether) or inconvenient (his cell phone can’t pick up a signal, and internet connections are poor). But when Mohan is sent on an errand by Kaveriamma to collect overdue rent from Haridas, a former weaver turned farmer living in a drought-ridden village with his starving family, he fully encounters India’s social and economic problems in human form, and the film’s already carefully constructed motif of water will begin to focus what follows. (Here one might recall that drought is the backdrop to the village’s misery in Lagaan.)

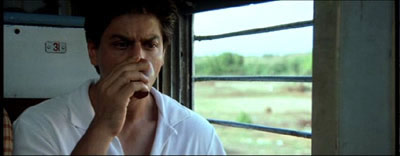

Mohan’s work at NASA is designed to prevent the entire planet from future drought, but is not designed to relieve the parched fields of present-day India; throughout the first half of the film Mohan is frequently seen – like any Westerner – drinking bottled water, but his emotional return to India is first signaled by his purchasing a 25 paise cup of – unfiltered, unbottled -- water from a boy on a train platform as he returns to Charanpur. Tapping a local spring, he realizes, will provide the necessary source for the village’s own generation of electricity, and the engineering skills that Mohan was offering to the world of the future will be redirected to what he is realizing might be his “home” in the present.

In many ways, Swades is a curious and surprisingly successful hybrid of the recent NRI (Non-Resident Indian) film and the progressive “social message” films of the Nehruvian 1950s. While the recent model typically affirms the essential Indian dil (heart) of globetrotting Indians armed with cell phones and Apple laptops, despite their lack of basic cultural literacy (such as how to tie a dhoti), the earlier model often focused on the collective development of independent yet still poverty-stricken India. Swades even invokes the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi and the ideology of the independence movement with an on-screen epigraph: “Hesitating to act because the whole vision might not be achieved, or because others do not yet share it, is an attitude that only hinders progress.” Swades thus acknowledges but – reasonably — cannot suggest a simple solution to India’s rural poverty: more practically, the film affirms the need for local attention to education and literacy, and dramatically demonstrates that electrification of at least a village can be achieved through hard and collective effort; towards the film’s conclusion, the internet and email are promised for the near future. Indeed, Swades at times directly invokes classic films of the post-Independence era such as Raj Kapoor’s Shri 420: both films include early scenes in which the playful hero joins and disrupts a rural class being taught by each film’s schoolteacher-heroine. (Mohan, after seeming to be ignorant of basic facts about India before the giggling students, reveals his detailed knowledge of his homeland to Gita a moment later.) The message of Lagaan for contemporary India – that members of different castes and religions can succeed when they come together as an all-Indian group – was displaced onto the mythic past of the first all-Indian cricket team. Swades avoids such displacement or allegory by locating its inspiring story firmly in the globalized, weblinked present and thus seems to implicate an audience that cannot keep its message safely in the past.

Critics (as well as producers) of Hindi film in recent decades have increasingly recognized that the NRI or diasporic audience constitutes a significant share of any film’s revenue, with a few films even proving more successful outside of India than within. A number of these films (as well as explicitly diasporic films like Monsoon Wedding and Bend It Like Beckham) have also made the NRI, once ridiculed or demonized in Hindi films, a positive figure, at least since Shah Rukh Khan’s groundbreaking role in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge in 1995. Indeed, although himself a native and citizen of India, Shah Rukh Khan has perhaps most consistently played the “positive” NRI in Hindi films, in no small measure contributing to his immense popularity among the diasporic audience he often embodies on screen. Swades might be understood as a new variation on this pattern: unlike previous films such as Pardes that (as Jigna Desai notes) often oppose a “good NRI” and “bad NRI,” Swades avoids such easy dichotomies, or perhaps internalizes them insofar as Mohan inhabits both roles, but without typical exaggeration in either position. Indeed, the film is clearly conscious of Mohan’s ambivalent status for its other characters: he is teased as “Mr. NRI” by his friend in Delhi when he requires a caravan to face the privations of Indian village life, and challenged more pointedly by Gita when she calls him a “Non-Returning Indian,” announcing her scorn for the man who embodies the “brain drain” of talented Indians who prosper by only using their talents abroad.

In fact, Swades in some ways functions as a rejoinder to the diasporic Hindi film set in England (such as Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham) or the United States (such as Kal Ho Naa Ho), which extends “Indianness” into landscapes that are fully inhabited rather than merely visited (usually in fantasy song sequences) by Indian characters. As Jigna Desai notes of such films, “displacement no longer necessarily functions as a marker of loss of Indianness.” In a more critical vein, Vijay Mishra has emphasized “It is one thing for the homeland to be constructed through the dream machine of Bombay Cinema. It is quite another for Bombay Cinema to create its own version of the diaspora itself and, through it, to tell the diaspora what it desires.” Swades offers another stage in this recent yet already familiar process: it not only constructs the homeland for its “local” audience, but creates “its own version of the diaspora” in order to “tell the diaspora” that what it desires is the homeland. Put another way, the film encourages its Indian audience to fantasize leaving for the West, and then returning home; for the NRI audience the film is presumably an even more complex, even guilt-inducing, call for return – perhaps to a home where many of the film’s “non-resident” viewers have never actually been. As discussions of the South Asian diaspora (such as Sunaina Marr Maira’s Desis in the House) have often emphasized, nostalgia – literally the pain of returning home rather than the simplified Americanized notion of the “good old days” – and rituals of “going back” are key components in the construction of diasporic (rather than immigrant, or assimilated) identities, and Swades is unusually perceptive in its recognition that Mohan does not long for a past he has learned to question, but for a new home that will be both easy and difficult for him to (re)enter.

As Arvind Rajagopal has argued, “NRIs invite metaphorical description in the way they encapsulate contemporary flows of money and desire.” Officially defined by the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act of 1973 in order to facilitate the “return” of money from any “person of Indian origin” to the homeland, the NRI has also been, as Rajagopal demonstrates, a central figure in the globalization of Hindu nationalism (Hindutva), specifically as a potential source of powerful financial and symbolic “expatriate nationalism” that has often, among other things, embraced the Hindu right’s appropriation of religion for political gain, including the redefinition of the epic hero Ram as a fierce Hindu warrior.

Notably, Swades undermines the revision of Ram and the related appeal to reactionary “expatriate nationalism” during the village’s Dussehra festival Ram-leela performance in which Gita plays Sita (herself an increasingly complex figure in contemporary Hinduism and Indian feminism). Mohan, to no one’s apparent consternation, and in his Western clothing, steps into Ram’s role before the local performers playing Ram, Lakshman, and Hanuman enter the pageant. Unlike the militant and muscular Ram of the contemporary Hindutva movement, Mohan is a romantic rescuer armed with communications technology rather than bow and arrow. (In this regard, the film bears superficial comparison with Apoorva Lakhia’s less successful film Mumbai se Aaya Mere Dost, which depicts an urbanized young man named Kanji, played by Abishek Bachchan, returning to his non-electrified village with a television set and satellite dish: after securing electricity, exposure to Hindi films threatens to disrupt the work of village life until broadcasts of the beloved Ramayana serial captivate the village. Swades evokes the live folk performances that preceded the teleserial and in effect re-stages one in the serial’s influential wake.) The undisguised fact that the “real” reincarnation of Ram is located in the body of the globalized NRI summarizes the film’s simultaneous invocation of and often daring revision of tradition. (The quieter suggestion that this Sita actually rescues this Ram also bears noting.)

The UTV Communications DVD of Swades is of excellent quality, with songs translated (into a choice of eight languages!). However, in what seems a misguided attempt to render the poetic quality of the original lyrics of famed poet-screenwriter-lyricist Javed Akhtar, the English translations of the songs employ a clumsy, “elevated” vocabulary that sounds like a bad Elizabethan poem or a parody of the King James Bible: “you” is rendered as “thou” and verb forms like “experienceth,” “concealeth,” “longeth” and “toureth,” abound(eth). Moreover, a bonus “English Transliteration of Songs” on the DVD as well as in an accompanying booklet provideth the same unintentionally comic lyrics. The DVD also includes a separate disc of extras, including deleted footage, auditions, and “Social Relevance Information.” The latter consists of a summary of India’s caste system “complied only for the purpose of the film and necessarily does not coincide with any other researched sources.” Truly interested viewers might nevertheless be encouraged to seek out “other researched sources.”

Works Cited

Jigna Desai, “Planet Bollywood: Indian Cinema Abroad” in East Main Street: Asian American Popular Culture. Ed. Shilpa Dave, LeLani Nishime, and Tasha G. Oren. New York: NYU Press, 2005.

Sunaina Marr Maira, Desis in the House: Indian American Youth Culture in New York City. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002.

Vijay Mishra, Bollywood Cinema: Temples of Desire. London: Routledge, 2002.

Arvind Rajagopal, Politics after Television: Hindu Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Public in India. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001.