TAAL

(“Beat,” 1999, Hindi, ca. 175 minutes)

Produced, Directed, and Edited by Subhash Ghai

Story: Subhash Ghai; Dialogues: Javed Siddiqui, Subhash Ghai; Screenplay: Sachin Bhowmick, Subhash Ghai; Music: A. R. Rahman; Lyrics: Anand Bakshi; Art direction: Sharmishtha Roy; Audiography: Rakesh Ranjan; Choreography: Saroj Khan, Ahmed Khan, Shiamak Davar; Cinematography: Kabir Lal.

In India, stories in which a boy-from-the-plains meets and falls in love with a girl-from-the-mountains—after which complications ensue—are as old as….well, the hills—or at least as old as the classical epics. In Hindi cinema, this theme has long been a favorite that has regularly generated hits, ranging from Raj Kapoor’s 1949 Barsaat (“Monsoon,” famous for its image of Nargis, as a Kashmiri maiden, swooning in the arms of the violin-playing poet-hero, which became the logo of Kapoor’s R.K. Studios), to Shakti Samanta’s 1964 Kashmir Ki Kali (“bud of Kashmir,” starring Shammi Kapoor as the runaway son of an industrialist and Sharmila Tagore as a flower-seller in the Vale), to 1985’s blockbuster Ram Teri Ganga Maili (“Ram, your Ganges is tainted,” again directed by Kapoor).

The basic scenario lends itself to a complex array of thematic polarities that have often been explored in Hindi films: e.g., the equation of woman with nature, purity, and tradition and of man with modern civilization and its attendant ills; the contrast between the rustic (both valorized as pure, natural, and indigenous, and critiqued as coarse, “junglee,” and backward) and the urban (again, both in its positive valuation as modern, educated, and progressive, and in its negative depiction as westernized, callous, and corrupted), and the tension between the regional or local (embodied in ethnic costume and cultural practice) and the cosmopolitan or national (expressed in the centrism of nationalist ideology and through a supposedly pan-Indian—although in fact mainly north Indian—urban lifestyle). In addition, such narratives often portray the supposed “innocent” sensuality and sexual forwardness of the mountain maiden both as a pretext for erotic spectacle and as a plot-driving motif; e.g., with a self-assertive Pahari girl boldly choosing an outsider, pardesi boy in defiance of her family and community.

Indeed, the heavy symbolic weight typically attached to the hero and heroine of such tales is suggested, in TAAL, by the names they are assigned: for the young “prince” from Bombay is called “Manav” (literally, “man” or “mankind”) and the maid of the mountains is “Manasi” (“mind-born,” the name of a high Himalayan river). A new twist given to the dichotomy here is that “civilization/urbanity” is also equated with the world of mass media and entertainment, especially the film and television industry (with MTV, a corporate tie-in, as its ultimate exemplar), which is both glamorized and parodied. Instant “stardom” is now another of the temptations that the modern metropole proffers to the innocent rustic maiden—though she can “escape” it, of course, through a suitable marriage.

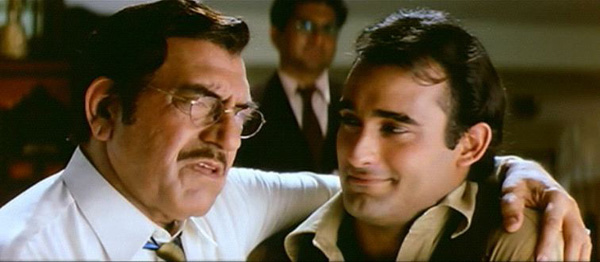

Like the heroes of many romances of the late 1990s, Manav (Akshay Khanna) is a “Non-Resident Indian,” London-raised (but speaking nice Hindi), and in fact visiting India (improbably) for the first time, together with his billionaire father Jagmohan Mehta (Amrish Puri) and assorted hangers on, including a sycophantic and calculating uncle and a shrewish sister-in-law (whose short, color-streaked hair immediately warns of the Too-Westernized Woman, an impression confirmed when she snobbishly compares the Himachal hill station of Chamba unfavorably to Scotland). Whereas most of the Mehta clan arrives in the hills (where they own a mansion and scheme to build an unspecified but sinister-sounding “project” involving foreign investors and billions of rupees) by limousine and helicopter, young Manav—who wants to “see the real India”—comes, complete with rucksack, in a second class railway compartment and perched atop the crowded roof of a bus. This earns him points, as does his fervent embrace, on arrival, of the shoes of Daddy, to whom he is wholeheartedly devoted—a real Indian boy, after all! He also loves his fluffy dog, Brownie (seasoned fil-um-watchers may guess that the latter will eventually play a key role as romantic go-between), and his toys, especially the fab new digital camera brought by Daddy from Singapore. Manav uses it to record his first, awed impressions of Himalayan valleys, and accidentally captures, in one such vista, a portrait of a stunningly beautiful young woman doing yoga asanas. Naturally (and in the great tradition of Imperial photographic documentation), he decides that he must have her.

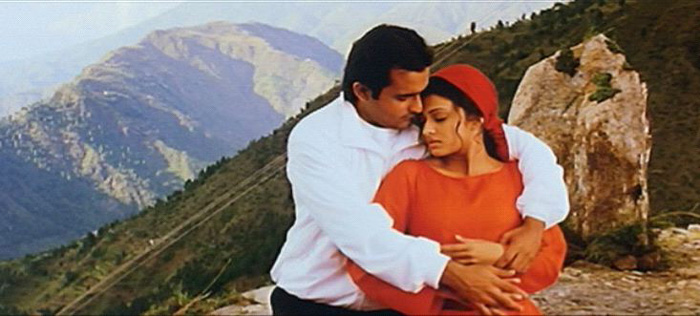

She turns out to be Manasi Sharma (Aishwarya Rai), daughter of the “poor” (by Mehta standards) but proud and carefree Himachali folk musician, Tarababu (Alok Nath), and herself a trained dancer and singer, as is revealed by the sensuous rainy season song Dil ye bechain (“these hearts are restless”). As inRAM TERI GANGA MAILI, Manav and Manasi meet precipitously (literally, when both nearly fall down a cliff), and he begins wooing her with quiet but unrelenting attentions—e.g., by passing her, during the otherwise engaging song sequence Ishq bina (“without love”), a Coke bottle (another corporate sponsor!) out of which he has sipped. (Cultural point here: this is not merely bad manners, but a violation of the strong Indian taboo against jutha, or food/drink contaminated by someone else’s saliva, so when Manasi daringly takes a sip it is somewhat akin to kissing Manav. Not surprisingly, this will follow ‘ere long….)

Manasi is at first reluctant to return Manav’s interest because of the social gulf that separates them, but she softens during a sensuous sunrise yoga lesson, which leads to some heavy petting and an exchange of promises. Meanwhile Mehta senior—who needs Tarababu’s influence with the Chief Minister of Himachal Pradesh for approval of his industrial scheme—has buttered up Manasi’s dad with a statue of goddess Saraswati to grace Tarababu’s struggling school of music, and has offered to help promote his career. After goodbye embraces all round, the scions of industry depart for Bombay, leaving the yokels to ponder whether promises will be kept.

A visit to the Big City quickly dashes their hopes. The wicked Mehta sister-in-law contrives to deny father and daughter entrance to the family mansion (which looks an awful lot like a five-star hotel lobby), leaving them waiting by the dog kennel in the sun, and then provokes an argument, at the climax of which the humiliated Tarababu strikes Mehta senior. Just then, Manav arrives on the scene and, misinterpreting what is happening and shrieking “My father is EVERYTHING to me!,” hurls his own stinging insults at both Tarababu and Manasi, telling them to leave and never return. (Tellingly, the “prince” makes no effort to find out what is going on and shows no pleasure at seeing his Beloved; he simply rushes to the defense of Daddy, whose offended Honor overrules all other considerations; the director seems to approve of this behavior. Cultural point….)

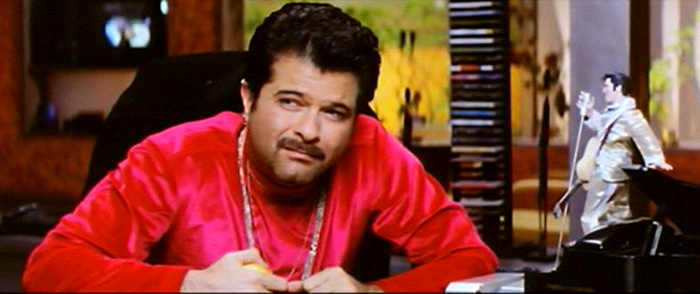

Despairing, father and daughter walk the crowded streets of Bombay until they wander into an outdoor arena where a rehearsal for an elaborate pop spectacle is in progress. To their amazement, they find that the assembled singers, dancers, and orchestra are performing a souped-up version of one of Tarababu’s own songs (Dil ye bechain), under the direction of Vikrant Kapur (Anil Kapoor), a hyperactive singer-dancer-director out of the mold of Rahul inDIL TO PAGAL HAI, only a bit older and more cynical. Like Rahul, he inhabits an extraordinary “studio” apartment-cum-soundstage-cum-corporate office, full of agile young extras writhing in spandex, and leads a postmodern life consisting of a series of grandiose gestures accompanied by nonstop Hinglish patter. Ushering Tarababu and Manasi into his office, he proceeds to explain the mysteries of “remix”—whereby folk melodies are plagiarized, orchestrated, and re-recorded to make millions for moguls like him, while their original performers get nothing. He has, he frankly admits, lifted Tarababu’s songs from Jalandhar Radio and released several profitable albums.

Kapur’s confession is of course an accurate description of what Bombay music directors sometimes do, and the insider parody of his portrayal (in the film’s strongest performance, which earned the versatile Anil Kapoor a “best supporting actor” Filmfare award) is enhanced by the fact that he is so visibly a “re-mix” himself: an international glam wannabe who toys with a mechanical Elvis doll while delivering his sermon on the joy of plagiarism, and dreams of winning an international MTV competition in Canada. Tarababu (who belongs to an older school that considers music a collective treasure and not a property for individual ownership or “copyright”) seems dazed by all this, but Manasi (understandably) takes heed of Kapur’s admonition that it is necessary, in the 21st century, to be “practical” rather than “emotional,” especially when he follows it up with an offer to give her a screen test and, pending its outcome, make her “a star of tomorrow.” With the cajoling of a worldly-wise and divorced aunt in Bombay, Tarababu and Manasi agree to Kapur’s makeover.

Manasi’s fast track to fame is charted through the extravagant production number Koi aag lage (“If fire breaks out [I don’t care]”), which ends with her performing before a crowd of thousands at the Filmfare Awards gala and being feted on MTV India. Poor Manav (now repentant after the servants clued him in on what provoked Tarababu’s outburst) watches on television with sad puppy eyes. Nevertheless, despite Manasi’s protests and her 3-year, multimillion-rupee contract that specifies that she will neither fall in love nor marry, Manav continues to pursue her (some would call this “stalking”). But wait! The no-marriage clause will soon be null and void, because Kapur himself, Pygmalion-like, falls in love with his own creation and pops the question. This provokes the film’s climactic crisis: which self-centered suitor will Manasi wind up spending the rest of her life catering to? The smug, baby-faced billionaire with the cute dog and abusive family, or the self-made pop impresario with the postmodern tribe and predatory business ethic? (Needless to say, the possibility that a girl of Manasi’s looks and talent might wisely choose to ditch both of these control freaks and go her own way does not even arise....) In the event, Manasi (looking properly dazed and confused) doesn’t have to decide: because, as is only proper, the boys work it all out for her! And this, of course, is a happyending.

Cultural points aside, the film boasts fine cinematography of the sweeping, never-a-still-moment school (Kabir Lal won a Filmfare Award for this), impressive pop-modernist choreography, and a strong Rahman/Bakshi score. Especially haunting is the title song, identified on the DVD by its first line (as is standard practice), Dil ye bechain, but with the more meaningful refrain Taal se taal mila (“two beats become one”). Kapoor’s cocky performance as the film’s only character of substance (and given the options, my personal favorite in the marriage competition) helps to keep the second half from dissolving into incoherence (e.g., as Manav "proves" his love by rushing into a burning building to rescue a scarf embroidered by Manasi, and risks death under the feet of her stampeding fans to rescue Brownie, etc.). Apart from the Kapoor character's scenes, dialog is not a strong suit, but a passingly pleasant moment occurs when Manav, after exchanging first intimacies with Manasi, discusses his impending departure for Bombay:

Manav: I know what you’re thinking.

Manasi: What?

Manav: That it’s just what happens in typical Hindi films: a boy comes from the city and falls in love with a hill girl. Then he leaves her and goes away.

Manasi: Then?

Manav: Then he never returns….. (embracing her) But this will never happen. This isn’t a film…its my truth, it’s my life!

Just how wrong Mr. Right can be will be proven after the interval: for all its gloss, TAAL turns out to be unsurprisingly typical, after all.

[The Eros International DVD of Taal is of high image quality and includes English subtitles for songs as well as dialog. As sometimes happens, the distributors even include them (for the hearing impaired?) when characters speak in English….and then manage, repeatedly, to mis-print what they are saying! (Thus, Kapur’s “Take it or leave it!” appears in the subtitle as “Take your own limit.”) Amazing sloppiness, or just another postmodern touch?]