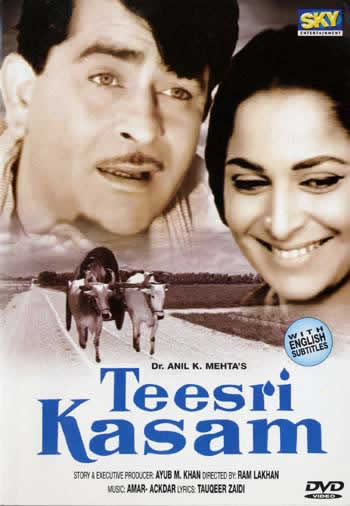

TEESRI KASAM

(“The Third Vow”)

1966, Hindi, 155 minutes

Directed by Basu Bhattacharya

Produced by Shailendra

Story and dialog: Phanishwar Nath Renu; Screenplay: Nabendu Ghosh; Music: Shankar, Jaikishan; Lyrics: Shailendra, Hasrat; Choreography: Lachhu Maharaj; Cinematography: Subrata Mitra

Like the earlier JAGTE RAHO (1956), also starring, but not directed by, Raj Kapoor this film combines the sensitivity of great Bengali artists with some of the conventions of mainstream Bombay cinema to produce essentially an art film with songs—no less than ten of these, and all remarkably beautiful and well integrated into the plot. Based on a well-known short story by Hindi/Bhojpuri writer Phanishwar Nath Renu (who also authored the film’s dialog) and shot by Subrata Mitra (who did the cinematography for Satyajit Ray’s early films), TEESRI KASAM features outstanding performances by Kapoor (who is remarkably subtle and subdued) and Waheeda Rehman, assisted by a superb supporting cast.

The story is set in rural north India, in the “cow belt” of eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar states. Its characters live in small places remote from India’s cosmopolitan centers, and nurture dreams and tastes (and vices) that are suitably to scale, but the film works wonderfully well to gradually draw viewers into this world and let them share in the emotional life of its denizens. Hiraman (Raj Kapoor) is a bullock cart driver—a provider of transport-for-hire in a world still largely untouched by paved roads and internal combustion engines. His pride in his animals and cart is, however, not unlike that of a long haul trucker with his new sixteen-wheel rig. After two bad experiences, transporting in one case smuggled goods (which are seized by the police) and in the other long bamboo poles (that cause a collision with a horsecart), he takes two vows, pulling on his earlobes in peasant manner, never to carry such things again. He is then asked to transport a passenger: an actress in a nautanki or folk theater troupe, on her way to perform at a small town fair; he agrees.

In the course of the long journey (for it takes some thirty hours to cover twenty kilometers via bullock cart!), Hiraman gets to know the actress, the radiant Hira Bai (Waheeda Rehman), whom he first mistakes for a fairy. Both have “diamond” (hira) in their names, and both are, indeed, gems in the rough: simple, honest people who carry the pain life has handed them with dignity and humor. Hira Bai (the suffix –bai often connotes a tawayaf or courtesan, for mostnautanki actresses, who displayed themselves on stage to ticket-buying male strangers, were assumed to be women of easy virtue) is the more complex of the two, and she is charmed by her driver’s blend of shyness, humility, and impassioned opinions (“the people of this area are all busybodies!”), as well as by his awed treatment of her, as a respectable “virgin” (kunwari) who must be shielded from the gaze of passers by. She also loves his singing of local folksongs, and begins calling him guru (“teacher,” since she wants to learn his songs) and meeta (“dear friend,” since they share a common name). Hiraman, whose child-bride died before she could even move in with his family and who hardly knows women apart from his sweetly-domineering sister-in-law, melts under her attention, while still retaining an awareness of the unbridgeable gulf that separates their worlds.

When they reach the fair, Hiraman meets several of his cartman pals and Hira Bai invites them all to attend the shows of the “Great Bharat Nautanki Company,” which has just hired her as its female star. These performances, in a tent-theater erected on the street of a dusty provincial town, evoke for the characters all the magic of vaudeville, grand opera, and cinema rolled into one—indeed, the commercial cinema’s debt to nautanki is acknowledged in an excerpt from the (often-filmed) drama of the lovers Majnun and Laila, and in the four songs Hira Bai performs on successive evenings, all of which also play exquisitely on the fluctuating hopes, desires, and inevitable loss that she and Hiraman share. As in the earlier sequences on the road, the camerawork slowly pulls us into the constrained yet complex world of the folk theater, revealing slightly more of its stage and set in each successive scene. Naturally, the beautiful Hira Bai attracts the undesired attention of a lascivious local zamindar or feudal landlord, and naturally Hiraman girds himself to be the protector of her (imagined) modesty—but don’t expect a predictable melodramatic denouement.

The songs are superb, from Hiraman’s establishing song Sajan re jhoot mat bolo (“O friend, don’t tell lies…for soon you will have to face God”), a bhajan-style “song of the road” that recalls Mera juta hai Japani in SHRI 420, or Dev Anand’s opening number in GUIDE. Duniya bananewale (“O Creator…why did you make this world?”) provides a melancholy commentary on the tragic folktale of the village girl Mahua, which Hiraman narrates to Hira Bai, interspersing the story with verses of the song. Hira Bai’s performance pieces, from the coquettish Pan khaiye saiya hamaro (“My lover is fond of paan”), to the heartrending Aa aabhija, raat dhalne lagi (“Come back to me, the night begins to wane”) display characteristic themes of nautanki even as they chart the bumpy road of her relationship with Hiraman, who watches entranced from the audience.

The author of the short story penned wonderful dialog, rather inadequately rendered in the subtitles, that evokes the multi-glossic milieu and self-effacing yet cocky humor of rural India. Hira Bai’s speeches are tersely effective in conveying her dilemma as a professional woman: her love of her craft (“I get the same intoxication from dancing under the lights that you get from driving your cart”) versus her longing for home, family, and respectability. There are also hints of the Don Quixote story, as when she tells the landlord, speaking of Hiraman: “You think I’m a prostitute, he thinks I’m a goddess. You’re both wrong.” Yet it is clear enough, to us and to her, which of the two projections she would prefer—but does she have a choice?

[Although its subtitles are only barely adequate, the Sky Entertainment DVD of TEESRI KASAM offers an excellent quality print of the film, and its songs are subtitled as well.]