TEESRI MANZIL

(“Third Storey”)

1966, Hindi, 158 minutes (according to DVD box; 172 minutes according to Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema)

Directed by Vijay Anand

Produced by Nasir Hussain

Story, screenplay, and dialogue: Nasir Hussain; Editing: Vijay Anand; Lyrics: Majrooh Sultanpuri; Music: Rahul Dev Burman; Playback singers: Asha Bhosle, Mohammad Rafi; Art direction: Shanti Das; Cinematography: N. V. Srinivas

The standard disclaimer that opens this stylish mystery thriller: “ALL NAMES & CHARACTERS IN THIS FILM ARE FICTITIOUS & BEAR NO RESEMBLANCE TO ANY PERSON LIVING OR DEAD" could hardly be more true. Though the Himalayan hill station of Mussoorie, where the action ostensibly transpires, certainly exists, it does not now nor did it ever contain hotels with Las Vegas style revues, soulful and pampered young drummers with Teddy Boy wardrobes, and high-heeled vamps in fur and silver lamé, nor was it ever located, as this film’s resort town patently is, somewhere in the Deccan. No matter; sur-realism reigns supreme here, and Vijay Anand’s fine eye and Hitchcock-homage vision, together with Burman’s bouncy score carries the day, even for those who are not Shammi Kapoor fans.

For those who are, this is one of the actor’s most applauded roles after JUNGLEE, pairing him with Asha Parekh and giving him plenty of opportunity to display his trademark manic-obsessive lover character. Here he is Anil Kumar, a.k.a. “Sona,” a.k.a. “Rocky,” a drumming and singing sensation who, together with his jazzy band and a lavish revue featuring dancer Ruby (Helen), packs ‘em in nightly at the posh Park Hotel. Unfortunately, a girl named Rupa, who is in love with Rocky but has been spurned by him, falls to her death from the hotel’s third floor (that’s British style, so the American fourth)—an apparent suicide. One year later, her younger sister Sunita (Parekh), believing Rupa to have been raped by Rocky, comes to the hotel seeking revenge—in the usual way, of course: by having her college girls’ hockey team attack Rocky with their sticks! Trouble is, Rocky has already fallen in love with Sunita, whom he met by chance on the train from Delhi, so he arranges for a band member to impersonate him for some days while he, using his real name of Anil, woos the obstinate girl as only Shammi can: by hurling himself in front of her, talking manically, making rubber faces, etc. He is aided from time to time by his well-heeled older friend, Prince Mahender Singh (Premnath) and frustrated by the pouting Ruby, who is madly smitten with him. Against all odds, Sunita does fall in love with him too—after he protects her, one Dark and Stormy Night, from a gang of rapacious thugs—but there’s still the problem of Rupa’s death, which may in fact have been murder. Did Rocky do it? Or Ruby? And what about the sinister Ramesh (Prem Chopra), Rupa’s jealous fiancé, who is also making a play for her sister Sunita?

It all gets sorted out, more or less, in a surprise ending, but the real delight is in the pop-hallucinatory mise-en-scene. Though the film’s treatment of character is conventionally sexist (narcissistic, romance-obsessed, but ultimately patriarchal-conservative hero-stud encounters a sequence of three “bad”—which is to say, independent and sexually forward—ladies, each of whom is, of course, destroyed), the visual regime is playful, innovative, and often erotic. The wicked camera work includes gazing at and through apertures of all sorts—eyes, lattices, and guitar soundboards—and the frenetic cutting sets a pace that manages to upstage even hammy Shammi. The baroquely incoherent sets, especially for the club numbers, might have sprung from the fevered brain of a downmarket Salvador Dali (though, of course, they are really Bombay Occidentalism’s idea, in 1966, of the last word in modern chic). In one costume bit during the first song, Woh hasina (“That beauty,” sung for Shammi by Mohammad Rafi), Helen appears, dressed as a pink Flamenco diva, in the pupil of an enormous eye, framed by lashes that are shaped into cruel-looking steel fangs, while Shammi in a silver tux blows soulfully on a tenor sax. A moment later, they are romping through a landscape littered with what appear to be beribboned Joan Miro sculptures, then on to a forest where giant pastel-shaded lamps with crooked stands surround a faux Henry Moore figure, around which frolics a troupe of Slavonic ladies and Mariachi men. (Alice’s Adventures might have turned out like this had she gone, instead of to Wonderland, to the Museum of Modern Art during an Ethnic Diversity festival.)

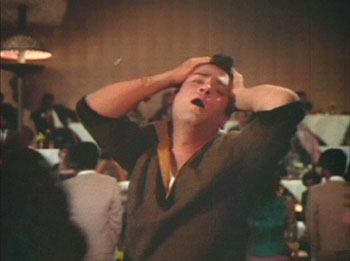

Another standout number is Aaja aaja (“Come to me, come to me”), performed in an equally pastichey “rock ‘n roll club” and featuring Shammi’s orgasmic twitching during the beckoning refrain, “aa-aa-aa-aaja, aa-aa-aa-aaja”—which is evidently contagious, since everyone begins to do it. (Lucky thing that, back then, no one worried about Sexually Transmitted Dances!). Other catchy tunes, performed in more standard mountain landscapes, are Deewana [mujh sa nahin] (“There’s no mad lover like me…”), and O mere sonare (“Oh my darling Sona,” the latter sung by Asha Bhosle for Parekh).

[The Eros Entertainment DVD of TEESRI MANZIL is of decent but not exceptional visual quality. Subtitles are adequate for dialogues, but unfortunately are not provided for the six songs.]