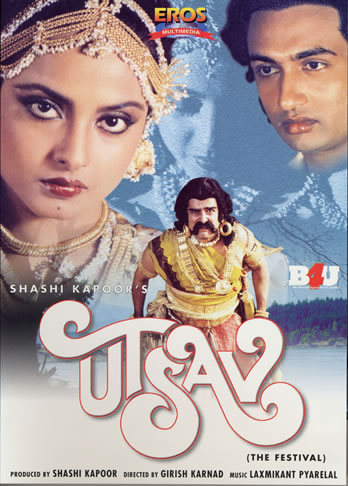

UTSAV

Directed by Girish Karnad

Screenplay: Girish Karnad, Krishna Basrur;

Dialogues: Sharad Joshi; Lyrics: Vasant Dev; Music: Laxmikant-Pyarelal; Cinematography: Ashok Mehta.

Produced by Shashi Kapoor.

Playwright, actor, director, and theatre scholar Girish Karnad conceived this film as a popularly-accessible tribute to the glories of Sanskrit drama, turning one of the most beloved of classical plays, the ca. 5th century “Little Clay Cart” (ascribed to Shudraka) into a contemporary spectacle with A-list stars and music by major filmi composers. Lavish sets and costumes, jewelry and hairstyles, all inspired by classical paintings and sculptures, evoke the glories of the Gupta age, while saucy dialog in contemporary (if properly Sanskritized) Hindi recreates the playwright’s satirical vision of the demimondaine world of the city of Ujjayini. By reminding viewers that, for ancient Indians, “pleasure” and “profit” (kama and artha) were right up there with “virtue” (dharma) among the principal Aims of Life, the film can serve as a refreshing antidote to the over-emphasized philosophical and mystical preoccupations of the much-studied texts of the classical period (e.g., Bhagavad-gita). Its Rabelaisian cast of characters — the voluptuous and talented courtesan, witty cat burglar, pompous monk, wild-eyed revolutionary — mirror those found in the worldly-wise story anthologies of the classical period (such as those translated in J. A. B. van Buitenen’s Tales of Ancient India), and thus bring to life their urbane world of fleshly delights.

As in modern Western adaptations of Greek classics, stage business is abundantly used to flesh out the script, and Karnad adds the clever touch of placing Vatsyayana, brahman author of the famous treatise on erotics, Kamasutra, in the midst of the brothel where much of the action unfolds. As played by Amjad Khan (the Gabbar Singh of SHOLAY), Vatsyayana is a portly pedant, a proto-social scientist who has taken a personal vow of celibacy, the better to detachedly study the sexual habits of human animals. He lectures the attentive prostitutes on how his planned treatise will immortalize their brief careers, and frets over not being able to get beyond the number 28 in his catalog of sexual postures, gushing (intellectually speaking) when an eager disciple hauls him upstairs to witness, through a transom, Number 29 in flagrante delicti — a scene that skewers, in one poke, both the pomposity and voyeurism of academic scholarship.

As in reel life, Bombay style, so in Sanskrit drama, a good story necessarily involves a number of cleverly-interwoven subplots. The handsome young brahman Charudatt (Manjunath Shekhar Suman) is a penniless musician, whose adoring wife (Anuradha) pawns her wedding jewelry to maintain the household, though she occasionally storms off to her father’s house in a pique. During one such absence, Charudatt is accidentally visited by the celebrated courtesan Vasantsena (Rekha, then publicly infamous as Amitabh Bachchan’s alleged mistress), who is fleeing from the lecherous and oafish Samsthanak (Shashi Kapoor, looking even paunchier than he did in HEAT AND DUST), brother-in-law of the tyrannical king of the city. While Vasantsena hides out in Charudatt’s courtyard, the two fall passionately in love. To foil would-be robbers when she departs for her brothel, she leaves her fortune in erotic jewelry (a garment-like set of gem-encrusted golden chains) in Charudatt’s keeping. These jewels — which change hands several times in a plot of Shakespearean complexity — will eventually serve as evidence to frame the hapless hero on the charge of having murdered Vasantsena, for which he will be condemned to death. Before the executioner’s sword is raised, however, there will be multiple thefts, mistaken identities, an uproarious (and beautifully choreographed) spring Festival of Love, and one tumultuous coup d’etat, masterminded by the revolutionary Aryak (Kunal Kapoor) and a handful of black-clad accomplices, whose terrific swordfights thrillingly display the techniques of South Indian martial arts.

The mega-happy ending of the Sanskrit drama (of the sort generally favored in Hindi cinema as well) is subverted by a poignant final twist, conceived by Karnad to more accurately reflect the constraints on the ancient courtesan's social role. Though a commercial failure, this noble experiment in updating a classic play abounds in visual delights and fine performances. And (to paraphrase Twain) whereas everyone talks about how Bollywood melodrama is vaguely indebted to Indian classical and folk theatrical styles, Karnad actually does something about (and with) it, showing us, with a sideways wink, their thematic and emotional (bed-)fellowship.