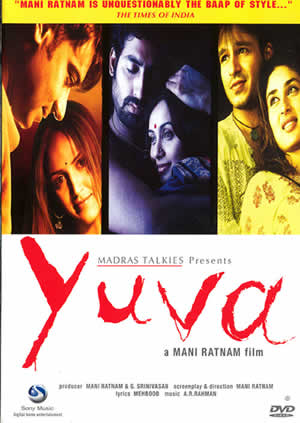

YUVA

(“Youth”), 2004, Hindi, approx. 160 minutes

Directed by Mani Ratnam

Produced by Mani Ratnam and G. Srinivasan for Madras Talkies

Screenplay: Mani Ratnam; Dialogues: Anurag Kashyap; Lyrics: Mehboob; Music: A. R. Rahman; Art direction: Sabu Cyril; Choreography: Brinda; Editing: Sreekar Prasad; Cinematography: Ravi K. Chandran

Evidently inspired by the acclaimed Mexican art film Amores Perros (Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, 2000)—from which it borrows the device of a traumatic narrative told from three different perspectives as well as a focus on the dystopian modern metropole of the global South (with Kolkata here substituting for Mexico City)—and using a narrative technique also seen in the American Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) and the German Run Lola Run (Tom Tykwer, 1999), Ratnam’s film uses multiple flashbacks to weave together three life stories that come together in a single horrific moment: an apparent murder committed amidst speeding traffic on Kolkata’s (a.k.a. Calcutta’s) recently-built Hooghly Bridge. The film opens with this incident that momentarily unites three apparent strangers, and then backtracks to tell the stories that propelled each man to this moment, which is serially re-presented from the perspective of each, with additional information being provided to viewers on each replay. However, after its fourth rehearsal of this incident, the film returns to a linear mode to follow events that ensue from the (as it turns out) unsuccessful murder attempt.

The first character to be profiled is the would-be assassin, Lallan Singh (Abhishek Bachchan), a streetsmart gunda (hoodlum), evidently from rural Bihar, who survives in Kolkata by brute strength, extortion rackets, and doing favors for his despised elder brother Gopal (Sonu Sood), a slightly more-refined gunda in the service of the corrupt politician Prasanjit Bhattacharya (Om Puri). Bailed out of prison for the umpteenth time by Gopal, Lallan promptly elopes with his middle class girlfriend Sashi (Rani Mukherjee), much to the dismay of her parents, but despite some romantic (and erotic) idylls (accompanied by the songsKabhi neem and Dol dol), Lallan refuses to give up his criminal ways to please his wife and her family.

After a brief flirtation with legal employment (when Prasanjit Babu sets him up in a gas-cylinder business after it is discovered that Sashi is pregnant), Lallan is pulled into Gopal and Prasanjit’s struggles with a group of idealistic students from Presidency College, who are organizing the suburban poor to defy the corrupt party boss in an election. As violence escalates between the two factions, Lallan is ordered by Prasanjit to eliminate the student leader Michael Mukherjee (Ajay Devgan)—the motorcycle rider whom he shoots at close range, while riding alongside him in an SUV, on the suspension bridge.

Michael’s story unfolds next. The son of a middle-class Bengali whose own political idealism cost his family dearly, Michael is a brilliant physics student and a political maverick who is prepared to defy the discredited and ineffectual law and to counter the establishment’s violence with his own.

His love interest is provided by Radhika (Esha Deol), a professor of French, who becomes peripherally involved in his campaign to organize residents of the Twenty-Four Parganas (an impoverished once-rural region that has been absorbed by Kolkata’s urban sprawl) to defy the corrupt state government—a campaign that, after considerable violence, results in the victory of a local woman championed by Michael. The heroic narrative of Michael’s political efforts (like that of Lallan’s criminal career) is interwoven with the romantic one of his relationship to Radhika, culminating in his “proposal”—not of marriage, but that she move in with him, in defiance of both their families—made just before his fateful ride across the bridge.

Unknowingly pursued by Lallan (who, like the hitmen in Pulp Fiction, is bantering with his accomplice about an irrelevant topic—here the impossibility of getting along with women—while preparing to commit murder), Michael briefly gives a lift to a distraught young lover, Arjun Balakrishnan (Vivek Oberoi) who is chasing his fleeing girlfriend Meera (Kareena Kapoor), and Arjun thus becomes an eyewitness to Michael’s shooting.

This leads to Arjun’s own flashback narrative, of a comfortably upper-middle-class Presidency student entirely without political consciousness (much to the dismay of his IAS officer father, played by Anant Nag), devoted to a Don Juan career of conquests (forty-two and counting), and in plotting his escape to the Promised Land of America. But a chance disco encounter with the vivacious Meera—a similarly elite girl whose self-confidence permits risqué flirtation even though she has already agreed to a semi-arranged match with a solid manufacturer from Kanpur—leads to True Love, which (as Hindi audiences well know) has the power to transform a man from a hyperactive, chattering, and grinning imbecile into…..a hyperactive, chattering, and grinning imbecile with heart, and with Determination! to win the elusive damsel. Though I jest, this frothy interlude—itself a kind of homage to a Hindi cinematic chestnut—is not without its charm, exemplified by the lovesong Anjaana anjaani (“two strangers”); Oberoi is suitably wastrel and hunky, and Kareena Kapoor is beguiling as a smart young lady who likes to have fun but (wisely) takes a long time to be convinced that Arjun is the Real Thing. Ironically, her conversion follows Arjun’s own realization—after the horrific episode on the bridge and his own unexpectedly heroic response to it—that love isn’t the only show in town. Indeed, Meera soon takes a backseat to Arjun’s budding devotion to the wounded Michael and his political cause.

Apart from its derivative play with chronology, Yuva invites thematic comparison with two notable Hindi films involving a trio of heroes: Farhan Akhtar’s Dil Chahta Hai (2001) and Manmohan Desai’s Amar Akbar Anthony (1977). Whereas Ratnam’s film apparently offers an “answer” to Akhtar’s glossy hit, countering the latter’s romantic idyll of three self-absorbed yuppies who exemplify a trans-national urbanity with more “realistic” protagonists dwelling in a grittier milieu, it offers even more striking parallels to Desai’s masala masterpiece, which extend even to the personas of the heroes. Arjun, the pretty-boy lover in pursuit of his dreamgirl, evokes Rishi Kapoor as qawwali-singer Akbar Illahabadi; the politically-active but aggressive idealist Michael suggests Vinod Khanna’s steely police officer Amar; and the scrappy subaltern who survives through crime (in AAA, the Goan liquor-seller and petty gunda Anthony) is symmetrically portrayed in both films by a Bachchan, père et fils—and in each case (despite many beguiling diversions and strong performances all around) it is this character who arguably steals the show.

Both films use a fast-paced and relentlessly entertaining format, deploying catchy and au-courant music sequences and all the technical tricks in the director’s arsenal of their respective yugas (and one has only to watch Ratnam’s climactic hungaamaa on Hooghly Bridge to imagine what the inventive Desai might have done with digital fx). Moreover, both offer a multi-stranded (and “multi-starrer”) narrative that relies on improbable coincidences. If Ratnam’s protagonists are not literally sundered “brothers,” they are nevertheless shown to be “related,” not only by their youth, sartorial preferences, and proclivity for mayhem, but by their common link to a fallen “father” figure (here the politician Prasanjit Babu substitutes for Desai’s obligatory smuggler)—a discredited patriarch who has turned to crime. Both also comment, within an entertainment-oriented format, on real socio-political issues of their eras, and both invite allegorical interpretation—though this will lead to very different conclusions concerning where the Nation is headed. In Desai’s idealistic universe—the vision of a filmmaker who matured amid post-Independence optimism—India’s religio-ethnic communities and economic classes recognize their essential kinship (symbolized by their blood bond to a suffering Mother) and unite to “make the impossible possible,” and to triumph over external and internal enemies—riding off (literally) into the sunset, singing about Love.

But in the more cynical and sanguinary vision of a director who matured after the Emergency, there can be no ultimate reunion of “lost” brothers except in a moment of hyperbolic and gratuitous urban violence—a carefully choreographed ritual whose driving logic is the glorification of brute strength, by which Michael finally establishes alpha-male dominance over the upstart Lallan and baptizes his convert Arjun as a grim protegé. The scrappy subaltern—with whom we sympathize despite his explosive outbursts (and Bachchan Jr.’s performance makes his dad’s Angry Young Man appear to have been only Mildly Miffed in comparison)—is denied the discovery of who his real enemy is, and is finally shown to have (literally) no future: his child is aborted, his wife abandoned, and we last see him in the same prison yard in which we first found him, awaiting likely execution for the killing of his elder brother. But for upper-middle-class boys, it’s a different denouement: Michael and Arjun get both the girls and the goods—here, election with two friends to the Legislative Assembly—and are last seen striding confidently, like a new set of Raghu brothers, into the halls of power.

Ostensibly, this is to initiate a renewed and more-righteous Raj—coded not only by Michael’s determined gaze and his friends’ tart riposte to Prasanjit’s “welcome,” but by the youths’ faded denim and khaki dress, which suggests both globalized cool and the rejection of the khadi-masked hypocrisy of their political seniors. But the Fallen Father (rendered with unctuous perfection by Om Puri) is still there, unembarrassed and unreformed, and given the fact that the boys have won by embracing his own violent tactics, I was left wondering whether his final speech—predicting that, having arrived, the young MLAs will soon either flee or conform, as other idealists have before them—is not uncomfortably prophetic. In this reading, Ratnam’s stylish film delivers the bleak message that, in today’s India, violence is inevitable, politics irredeemable, and nothing (except fashion) is likely to change.

[The Sony Music DVD of Yuva offers a superior quality print of the film, and tolerable subtitles—though viewers will have to use some imagination in reconstructing Lallan Singh’s colorful slang—are provided for both dialog and songs.]